The Franck Violin Sonata, composed in 1886, is a chamber work that affords pianists the opportunity to perform over and over again. Not only is it a staple of the violin repertoire, just about every other instrument has co-opted it for the stage: cello, viola, double bass; flute, saxophone, bassoon; there is even a version for solo piano by Alfred Cortot.

César Franck (1822 - 1890)

Technically, the Sonata is fascinating on many levels: how can this very complex, four-movement cyclical structure with an advanced harmonic and contrapuntal language present as the most compelling, direct, lyrical music, with four distinct moods that form their own narrative? Franck’s greatest achievement is that the composition technique can be completely forgotten in the experience of listening. In spite of that, it is interesting to me personally, to understand the nuts and bolts of how the piece actually works, how it creates those haunting feelings and magical moments. There are many analyses of the form as a whole, exploring the hidden relations between the movements, but I have not found a detailed analysis of the first movement, so I thought I would try and do so here.

Hopefully this would have some value for pianists who want to understand this movement at a deeper level and also who find reading some of the many accidentals and chords troublesome or confusing if not daunting in some cases. I am not a music theorist so if there are any errors or misnomers please reply in the comments or drop me a line.

Features

The sound of Franck’s Violin Sonata is very distinctive, and on closer examination the first movement has some definite features that contribute to its profile. In terms of harmony, there is a proliferation of ninth, German sixth, and diminished chords. Many root position chords are also dressed up with the added sixth, though it tends to resolve into the triad. The ninth, sixth and diminished chords contribute at times by clouding the definition and destination of the harmony; by leading surprising but coherent modulations; and for muted dramatic effect.

Eugene Ysaÿe, the work’s dedicatee

Overall the character of the first movement is one of fluidity and intimacy, though not without grandiloquence. Melody and harmony are always linked in any Classical piece, but here to a deeper degree the intervals of the melody are reflected in the harmonic relationships. The time signature and flowing character have a kinship perhaps with Beethoven’s Piano Sonata op.101, and its first movement, also in A major.

Clearly, a feature of the chamber style is the independent roles that the piano and violin play. Thematically, the piano has material reserved for it alone; the violin’s main material is only echoed or dimly suggested in the piano. Each has its own distinct character.

Form

Instead of the usual sonata-allegro form, the first movement manifests as a rounded binary. There are two main sections as well as two main themes, the first presented by violin, the second presented by piano. Eventually they merge together, revealing a hidden psychological affinity. The relationship between the two instruments artistically suggests a delicate dialogue between two characters.

The basic form can be described as this:

m.1-62:

exposition of the two main themes, cadential material leading to recapitulation

m.62-117:

recapitulation of the two main themes transposed, somewhat altered, and ending with the same cadential material (a “composed cadence,” often found in Baroque music like the Well-Tempered Clavier, for example the Prelude in A-flat major, Book II; the cadences are all transpositions of the same material)

The first part breaks down into these main events:

m.1-4:

brief piano introduction, on the chord of E9 (V), hinting at the intervals of the first theme

m.5-30:

violin presentation of first theme, with sequential modulations eventually leading to cadence in E major (V)

m.31-46:

grand piano presentation of second theme in E, repeated with changed character and texture in f# minor (vi), and leading to a cadence in c# minor (iii)

m.47-50:

violin re-enters with the first theme, mingled with the continuing fluid texture of the piano’s second theme accompaniment - a hint at how the movement will close

m.51-62:

cadential material that Franck later uses as a whole unit, a “composed cadence” - a technique derived from Bach’s Preludes & Fugues - to close the second part of the binary structure

The second part is a recapitulation, with a difference in direction and key:

m.62 - 88:

violin presentation of first theme, with some varied texture in the accompaniment, and sequential modulations heightened by more melodic ornament and wider spaced piano chords, eventually leading to a cadence in A major (I)

m. 89 - 99:

grand piano presentation of second theme in A, that is deflated and interrupted by the violin’s early re-entry in m.97; the cadence at 99 is incorporated again in the last measure*************************

m.100 - 117: Coda:

featuring the second theme on an A pedal tainted with chromatic neighboring tones; from m.106 it dissolves into the first theme, and the cadential unit from m.51 is repeated in a transposed key. Whereas in the first part it was played by piano solo, now the violin joins to re-inforce, two octaves higher than in m.99, and without the chromatic passing tones of m.99, for a final contrary motion melodic cadence to A (violin’s descending interval against the piano’s ascending).**********************************

Below, musical examples will support this text.

Form, Melody and Harmony

Again, the principal profile of this movement is the mirrored nature of the form (two parts, in rounded binary) with the melody (two distinct characters that can also mingle together) and harmony (related directly to the intervals of the melody).

The principle interval is that of the third, which is first outlined in the piano introduction (m.1-4), along with the complete octave range of the upcoming melody, and then presented as a complete melody by the violin:

The thirds are bracketed ; the piano’s melodic range also stretches an octave from F# - F# as then fulfilled by the violin. Although unmarked, the upper pitches of the treble and bass chords also move in thirds.

The opening harmonies are also related to the melodic interval. The first chord we hear is E9, itself a stack of thirds, and not knowing in our ear yet its overall function or identity, it creates an ambiguous effect (similar to Beethoven’s Piano Sonata op.31 no.2 first movement, which opens with a ii7 chord in E-flat). The bass oscillates from E to B, suggesting E as the main tonality; two bars later within the violin’s melody, in m.6, we hear also a b minor (ii) chord in root position. But all of the pitches in b minor are already present in E9, and those pitches are also the same that constitute the melody:

E9 contains all the pitches of b minor as well as the opening of the violin’s melody.

Here melody and harmony are perfectly intertwined, and a sense of inviting mystery established. The interval of the third is the most prevalent, in harmony and melody, and formally as well: after a somewhat weak 6-5 cadence on A major (I) in m.8, the music moves sequentially to touch on C# major (III, or VI/V), a third away (the mediant to A):

Passing through C#, the mediant, which is driven by the use of the German sixth chord.

The main tool driving this sequence is the German sixth chord, which in Classical practice usually precedes and emphasizes a 6-4 - V - I cadence. Here Franck puts it to work chromatically, passing through it indeed to V7, but in m.11 the German sixth, instead of leading to a 6-4 chord on E, chromatically shifts into the C# region (m. 12 V/C#).

Note also in m.9-10, and sequentially afterwards in m.13, that the German sixth chord is preceded by a diminished chord on the second beats. Those two harmonies, the German sixth and diminished, are only one pitch away (F# - F natural), meaning in a way their destination - the V7 chord of m.11 - is preceded by two appogiaturas. Sure enough the sequence ends not with another German sixth but a diminished chord taking us in m.16 to B major (II, or V/V), and probably indicating that we have already modulated to E, while barely so far touching on A, the main key.

The harmonies from m.17-m.27 are of particular, unexpected beauty, and in some ways defy traditional analysis. In m.17 we return to a V9 chord, this time with a lowered ninth, and in the E (V) region; the chord at m.18 is basically A major over a B pedal; perhaps it is an A9, or IV9/V with the seventh (G#) omitted; but it hints at the Classical and Baroque tradition of reminding the listener of the tonic before a decisive formal modulation to the dominant; afterwards, retaining the pedal B, another V9/V chord leads to an implied cadence on E, a ninth chord with a melodic appogiatura on A# (m.20), with the E sensitively omitted, creating an exquisite feeling of partial resolution. Sequentially the same events happen in m.21 - 24, transposed to the F# region (the submediant to A):

m.16 - 24, sequential modulation in the regions of E (m.17-20) and F# (m.21-24)

A sudden hushed pianissimo in m.25 brings the F# chord in root position, with added seventh, leading into an altered circle-of-fifths modulation (c#7 in m.26, F#9 in m.27, B minor 9 in m.28, passing A 9 in in m.29 and fully realized V7/V in m.30) to the decisive cadence on E.

An altered circle of fifths progression to definitive cadence in E and the end of the first theme. The chord in m.28 is sometimes notated with a D#, but according to the 2016 Henle edition, that was a later addition and not present in any original source or first edition.

Measure 31 brings the second theme, stated by the piano, and establishes that the violin and piano are two separate characters of the same drama. It couldn’t be clearer, thematically; as the movement progresses, you’ll notice the violin never has the second theme material, but the piano will dissolve into the first theme. However, they are linked by way of contrast: the falling seconds of the piano theme (m.32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37) are an echo and reversal of the rising seconds in the violin (m.20, 24); also in general the violin’s theme rises at phrase endings, while the piano descends.

From m.31 to m.39, the piano sequences melodically in thirds (m.31, 33, 36 in octave displacement) and eventually has a true cadence in f# minor. Along the way, chromatic tones and substitute V chords introduce new key areas and shades of feeling. The final chord of m.32 seems to be an A9 (V/D) with the A omitted. The D chord of m.33 is seventh’ed, and sequentially the final chord of m.34 seems to be a C9 (V/F) with the C omitted. The F chord of 35 is seventh’ed, and oscillated with its major submediant (Db), which of course enharmonically is V/F#, where we end up after the simple cadence of m.38.

The second theme, expressed by the piano solo: the characteristic falling seconds are marked with tenutos (they contrast with the violin’s tendency to rise at phrase ends); the larger melody moves sequentially in thirds from pick-up to m.31; pick-up to m.34; and pick-up to m.36 (octave displacement). The V9 chords omit the roots, but adding them in gives clarity to the analysis. Melodically the piano begins in full octaves and chords, and reduces texture until single notes in m.38.

It should be noted that along the way, in these 8 bars, Franck also succeeds in reducing the piano texture, melodically from octaves in the right hand first to single notes over a spread chord, then shrinking that spread chord to two simple voices for the cadence. From m.39 - m.51 a new texture is then achieved, a flowing sixteenth note harmonic pattern somewhat prescient of Rachmaninoff. The second theme is now considered from a different angle, reduced to a single note melody, molto dolce, in large-scale echo effect. Eventually in m.47 we end up in c# minor, after the simple cadence of m.46 that incidentally has the simple bass line from m.38, inverted.

The second theme is echoed in f# minor, with a more chromatic baseline, producing unstable diminished chords in place of the root chord resolutions in m. 33 and 35. The individual notes of the bass line in m.46 is a simple inversion of m.38.

The bass line in this character transformation is more fluidly chromatic, leading the modulation. Perhaps one can say that the melody and harmony are out of sync, in a way: the falling seconds of m.41 and 43 indicate the previous phrase’s appogiatura and resolution on 6-5, but the “resolution” on the second beat of those measures is in both cases a diminished chord. It isn’t until m.46 that the harmony and melody agree.

At m.47, in c# minor, is the magical moment where the first theme appears, floating over the extremely delicate, wide-spaced arpeggios introduced by the piano for the second theme in f# minor. Answered canonically by the piano (foreshadowing the fourth movement), the aura of intimate dialogue is re-established, and shown to have as much compelling power as the grand assertions of the piano from m.31.

A seventh is added in the bass, in m.49, which turns out to be a passing tone before halting on an A# half-diminished chord, in m.50. From here a three-part sequence will lead the bass line to a pedal on the dominant E. Somehow, though, the passing harmonies give a static, pensive feeling. Franck here is manipulating the German 6th chord in a different way, morphing it into half-diminshed chords. German 6th chords in E, D, and C are treated this way:

Sharing the same lower note (in German 6th the third inversion, in half diminished the root) the half-diminished chords are essentially unresolved appogiaturas of the German 6th, theory-wise, and function as pivots into their respective tonal regions. When the bass line reaches E, it’s only a small chromatic adjustment to turn the C major chord into an E with a minor 9th, decorated melodically in a hermetic chromatic way, “resolving” into the E with a major 9th, the recapitulation of the opening harmony:

This entire passage, from m.51 to m.63, will be used as a block from m.108 to close the movement. These kinds of “composed cadences” are typical in the Well-Tempered Clavier, for example in the d minor Fugue in Book I. While the second time through the composed cadence ends safely in A major, how can the re-appearance of the E9 chord, as recapitulation, in m.63, feel like the resolution of the cadence even though the bass remains static and the harmony is still in the dominant? I think the disappearance of the soprano’s chromaticism, and the return of the familiar opening theme, create the feeling of resolution more than the harmony. On one hand a minor ninth is cancelled out by a comfortable major ninth, and on the other, theme takes precedence, a Romantic notion over a Classical one.

From m.63 to m.93, the same sequence of events follows the opening, with some minor differences, The piano has new textures, like widely spaced, activated chords in m.63 - 66, in place of the original static chords - the material has gained deeper meaning, reflected in the texture. Melodically too in m.71 the recapitulation features a more fleshed-out version of the original.

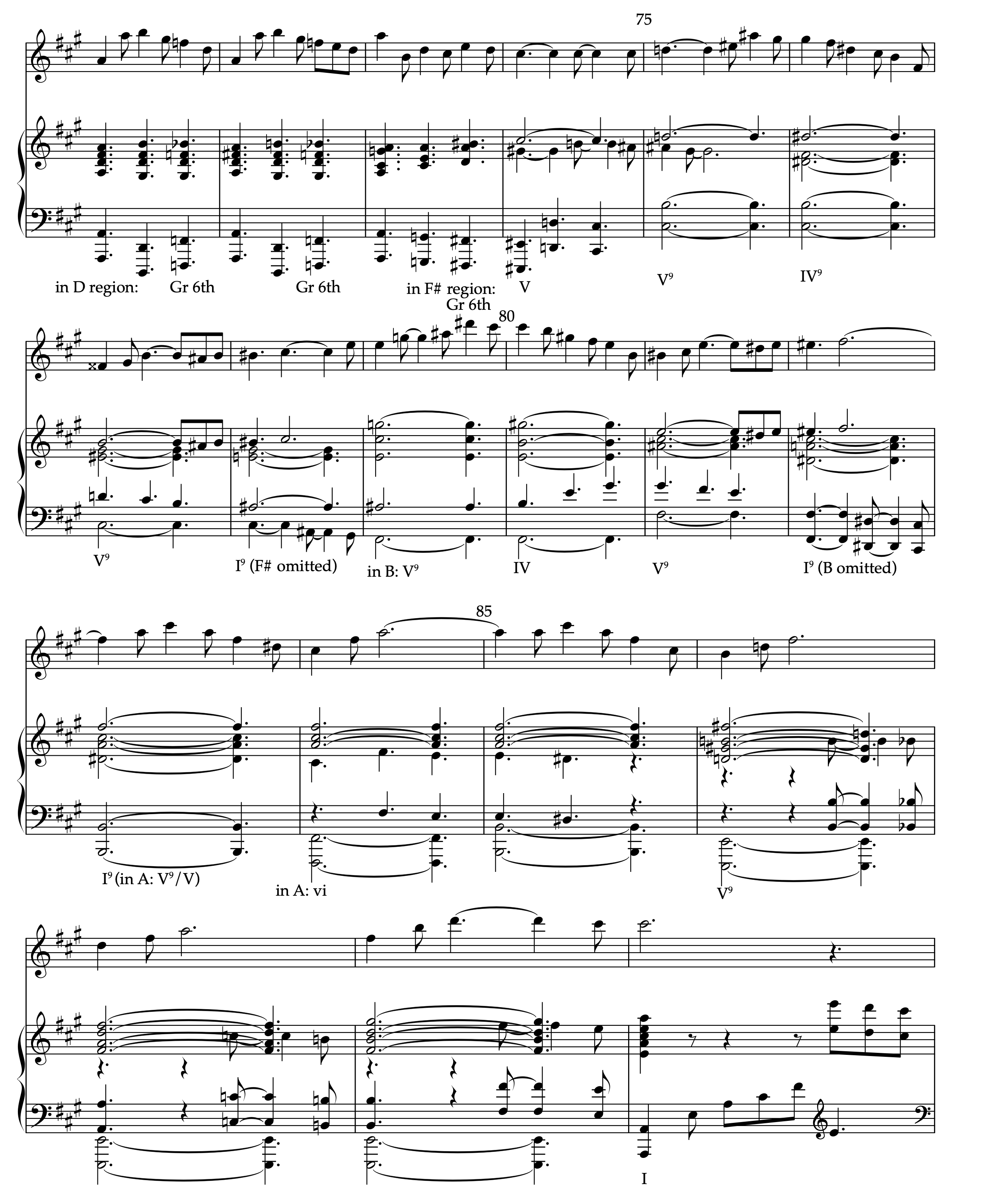

Starting from measure 71, the violin’s recapitulation has a more fleshed out melodic line. The original sequence is reharmonized to pass through regions of D (m.71 - 73), F# (m.74 - 78), B (m.79 - 83) and finally finding the dominant pedal to A, with the familiar E9 chord.

As expected the chain of modulations from m.67 - 88, analgous to m.9 - 30, are re-harmonized, this time passing through the regions of D, F#, and B, until finding the dominant pedal in m.86 for the modulation to the second theme, this time in the home key of A, in m.88.

The reappearance of the second theme is notable mainly for its transformation of character; whereas in m.31 Franck directs us to play it sempre forte e largamente, here it is accompanied by a constant diminuendo - diminuendo right from the start in m.89 and continuing with sempre diminuendo in 92. The length of the piano solo is cut in half; after meditating on whether to find solace with C# or B#, the violin re-enters and directs the cadence to A major (the violin’s melody also ends with a falling second, for the first time, rather than rising intervals):

The recapitulation of the second theme, again as piano solo, features a deflated character and shorter length than the first time around; the hesitant slurs in m.96 are analyzed literally, but probably their chromatic nature is more important than any chord symbol. The violin’s re-entry is accompanied by a chromatic descent in the bass, m.97, that leads back to A, and the violin ends its melody in m.100 with the falling seconds so far reserved for the piano’s expression.

The story of the recapitulation seems to be the dissolution of the grand character of the second theme. After the unsure harmonies of m.96 and the violin’s early re-entry, the second theme does return, now poisoned by dissonant neighboring notes disturbing the bass, and the melody falling sequentially in thirds rather than rising (from E in m.100, from C in m.103, and from A in m. 105). Measure 106 brings the final disappointment, as the piano dissolves downwards in a g# half-diminished chord (or the familiar E9, with the E omitted), into the “composed cadence” from m.55.

The coda of the first movement features another statement of the second theme, this time tainted by dissonant neighboring tones in the bass (marked with accents). The second theme now sequences downwards in thirds, until dissolving into the pitches and intervals of the first theme, in ms.106-107. From 108 to the end, the “composed cadence” of m.55 is repeated, transposed and with a new ending.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

The characteristic sound of this movement comes from the many kinds of German 6th, half diminished, and diminished chords. Small alterations in one, will blur its identity into another. Major and minor intervals also add sensitive color, and prevent a feeling of saturation or repetition. Often, these chords are used in substitution of simple harmonic procedures: 6/4 - V - I or IV - V - I cadences, or circle of fifths modulations and sequences.

In a way the inner workings of the first movement are very simple, even if employing more tools than typical Classical harmony, such as the frequent mediant relationships. But through exquisite artistry Franck has ornamented simple procedures with a mosaic of chromatic harmony, allowing varied moods and a clear musical narrative.

The division of the melodic material, of first and second theme between violin and piano respectively, is notably rejected in the second movement, where the instruments often play melodically in unison. The fourth movement of course is the famous canon between the two; the third focuses on melodic variations of the first movement’s theme and is focused mainly in the violin.

I think the way he treats the two instruments, first as two, then as one, and then finally as one following the other, is a major reason why this piece is so dominant in chamber music repertoire. The narrative arising from the interaction of the two instruments is easy to grasp, but also satisfying to execute.