Visions de l’Amen, for two pianos

I. Amen of Creation

II. Amen of the Stars, of the Ringed Planet

III. Amen of the Agony of Jesus

IV. Amen of Desire

V. Amen of the Angels, Saints, and Songs of Birds

VI. Amen of Judgment

VII. Amen of Consummation

The premiere of Visions de l’Amen at the Charpentier Gallery

Visions de l’Amen was composed on commission in 1943, quickly, and premiered that same year with Yvonne Loriod (the works’ dedicatee) and Olivier Messiaen on pianos one and two, respectively. It premiered on the series Concerts de la Pléiade, which was a cultural center for new music in the 1940’s, premiering almost one hundred pieces, many of which were unpublished. Visions was not published until 1950. The premiere was a cultural event unlike anything we see today, a packed hall attended by colleagues and luminaries such as Francis Poulenc, Arthur Honegger, Christian Dior, and many other artists and politicians whose names would be known to students of French history.

Also foreign to our times is Messiaen’s overall artistic reaction and personality in the face of the widespread devastation of World War II. In the midst of that all-encompassing war, and local occupation by the German army, he wrote music reveling in the joy of the eternal. His most famous work, the Quartet for the End of Time, was composed in 1940 in a POW camp (not a concentration camp is it is sometimes lazily called), and celebrates apocalypse as a return to all that is timeless and sacred. It was that work and its rapt reception that established Messiaen as a cultural figure, elevated from a brilliant church organist to a unique voice for the times. Maybe it could be said that his belief in the eternal was his most prominent characteristic as an artist, in an age of newly invented systems like serialism and what seemed like collapse of history.

In 1944, he detailed some of those beliefs in a short treatise, Technique of my Musical Language. Along with analyses of his recent works, including Visions, he set forth his interest in ancient Hindi rhythms (found in the 13th-century Sangita Ratnakara), in Gregorian chant (systemized by the monk-philosopher Dom Mocquereau), birdsong (in the next decade painstakingly notated by Messiaen himself) and his own research into “modes of limited transposition,” scales that could only be transposed a certain number of times before endlessly replicating themselves.

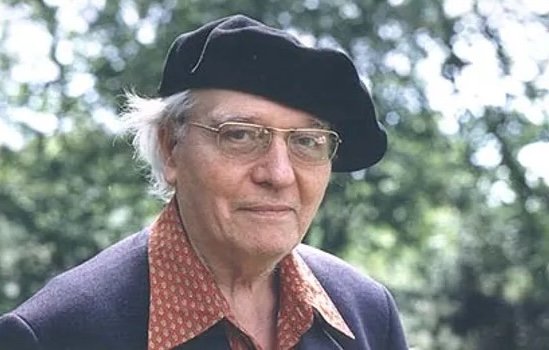

Even a glance at photographs would reveal how he wore his influences on his sleeve, so to speak. The beret of the French bohemian, above the severe glasses of the pre-Vatican II church intellectual. The exotic batik shirts, bright colors like the birds he loved so well, underneath the professorial tweed jacket. The occasional ascot or huge scarf of a dandy, as well as the constant pad of paper and pen for musical notation.

Messiaen notating birdsong

Messiaen in beret and batik

Messiaen in the 1940’s

His range of reading and influence was so vast, it is hard to fathom. His own extensive written and spoken commentary on his music was full of imagery and Easter egg references to the ideas that informed his work. He was critiqued in the press for his lengthy spoken exegeses before performances, laying out all the elements that went into the composition at hand. Visions is representative, being formed, according to Messiaen, of Catholic theology of eschatology, Hindi rhythmic palindromes and ancient Greek poetic meters, birdsong, Scripture, planetary astronomy, birdsong, and so much more, all harmonized and organized within the modes of limited transposition.

People often comment on his synesthesia, the association of specific colors with music, but I think it really goes beyond colors - all he absorbed from those readings were associated synaptically with musical visions; the source of influence and the proceeding musical image were inextricably linked in his mind. The result was vast musical structures littered with intellectual road signs that most audiences would find a bit baffling. But the enjoyment of his music is not dependent on understanding or even recognizing these sources, because ultimately he transcended them and translated them into a purely musical experience.

The modes of limited transposition are a good example. In his own published analyses, in both the Technique and the later Treatise on Rhythm, Color and Ornithology (not yet translated to English) he shows how passages are derived from this or that mode, in this or that transposition. Dense, complex chordal passages are a kaleidoscope of inversions and transpositions. That tells you what scales lie behind the text, but not why. Why mode three, in second transposition, for seventeen sixteenth notes, followed by three eighths of mode four, and so on? In the end the modes were the medium, but the medium was not the message. He mastered them to such an extent that I imagine the resulting chords were like three-dimensional objects for him, that he could invert and transpose at will, at any time. They actually inform very little about his art.

Visions de l’Amen did have one specific literary inspiration, a text by mystical theologian Ernest Hello called Words of God. Hello considered the word “Amen,” and saw it in a sacred symmetry: “Amen, word of initiation, of mediation, of consummation - Amen, word of Genesis, which is the Apocalypse of the beginning; Amen, word of Apocalypse, which is the Genesis of consummation.” In the preface to the musical score, Messiaen gave his own personal interpretation of that quote:

“Amen, it is done. The act of creation.”

“Amen, I submit, I accept. May your will be done!”

“Amen, the wish, the desire that you give yourself to me and I to you.”

“Amen, it is, all is fixed forever, consummated by Paradise.”

In the seven movements, Messiaen wanted to depict the “life of creatures who say Amen by the very fact they exist” and evoked in the titles and musical imagery stars, ringed planets in orbit, birds, Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, angels, saints, and bells: carillons and giant bells of final judgment.

The movements are organized as a sort of altar triptych,: in the center is the Amen of Desire, desire that is the result of all creation and that seeks consummation. On either side are three movements balancing out the triptych: Creation (I.) and Consummation (VII.) as beginning and end; the vastness of the stars and ringed planets (II.) balanced out by hosts of saints and angels and birds (V.); and the Amens of submission in the agony of Jesus (III.) and the ultimate judgment (VI.)

Seen another way, the structure as a whole could suggest a chiasmus, a hidden reference to the cross:

Hidden inside each individual movement are also an array of symbols, musical symbols that do so much to create the overall atmosphere. The main theme of the piece, what he called the “Theme of Creation,” recurs throughout:

I. Amen of Creation, m.1-8

And its phrasing is recalled by the Theme of Desire, though having become a little less four-square and more tender, more malleable:

IV. Amen of Desire, m.1-4

Beyond those clear themes, musical representation is happening on a whole other level. The birds appear first in the second movement, out in the universe with stars and whirling planets:

II. Amen of the Stars, of the Ringed Planet, m.

But are seen explicitly in movement five in their own habitat, in an extended passage of shapes common to the chaffinch, passerines, serin, babbling warbler, and blackbird, according to Messiaen in his Treatise:

V. Amen of the Angels, Saints, and Song of the Birds, m.

From that more literal representation of birdsong, Messiaen extracted pitch sequences that appear in other movements but completely transformed:

VII. Amen of Consummation, m.

IV. Amen of Desire, m.

No audience would be expected to perceive this, and it is even difficult for the pianist to make the connection, even if they might have a jolt of recognition and a sense on the edge of discovery. Messiaen is not Wagner, using recognizable leitmotifs to tell a story. Rather he seems to attach symbolic importance to the notes themselves. It invites a certain poetic interpretation: that the birds are present not only in their time and place but throughout all times and the universe, all places. They represent through their song and its transformations something eternal. From God, to the bird’s mouth.

As another example of musical symbolism, the end of the Amen of Desire features the languorous, satisfied Theme of Desire under the afterglow of a delicate, crystalline canopy of harmony:

IV. Amen of Desire, m.

However that beautiful harmony was actually first heard in the previous movement, the Amen of the Agony of Jesus submitting to his fate in the Garden of Gethsemane with the exact same pitches but in a different rhythmic context:

II. Amen of the Agony of Jesus, m.

“‘Father, if thou be willing, remove this cup from me: nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done…’ And being in agony he prayed more earnestly: and his sweat was as it were great drops of blood falling down to the ground.”

Over all love, hovering over bodily and spiritual desire, is the transformation of Jesus’ agony, Messiaen seems to suggest. His music is literally infused with his theology, and all the “techniques” of modes and rhythms and chords have been put to service for some greater purpose.

I think this goes some way in explaining the appeal and popularity of his music. From the forties onward he commanded large audiences and devoted performers. The critic Virgil Thomson hit the nail on the head in his description of Messiaen’s appeal: “His music rises to the heavens and brings down the house.” Even if the symbols are hidden so deeply that they can’t be apprehended, they are all part of a specific musical universe that he created. His music is multi-dimensional: it has atmosphere and physics, exists in space and time, but with a hidden depth leaving us with an indelible musical image, a sense that space and time have been transcended.